|

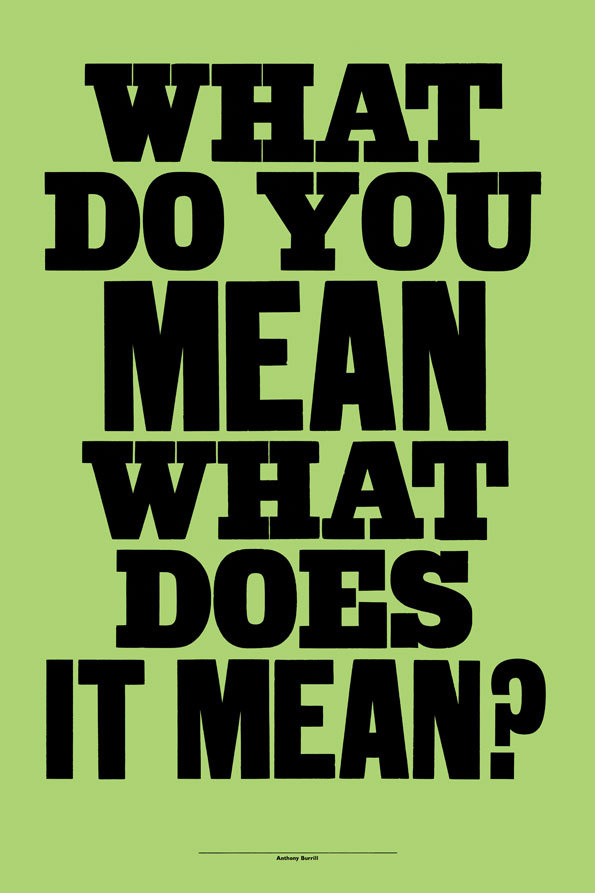

| The power of rhyme. |

"Remember these words:

If it doesn't fit, you must acquit."

If it doesn't fit, you must acquit."

For emphasis he said, "Remember these words." But that wasn't necessary. Most everyone remembers them to this day.

Rhyme has a special effect on our brains. It's called the "rhyme as reason" effect, or "the Keats Heuristic" after the poet. Various experiments have shown that people judge a saying or aphorism as more accurate or truthful when it rhymes. It also works in advertising and in product names.

Consider:

The power of rhyme is perhaps why we use it so often with little children. The babies of pregnant women who read "The Cat in the Hat" by Dr. Seuss repeatedly during their last trimester recognized the verse when they were born, distinguishing it from verse that didn't rhyme.One if by land, two if by sea. And I on the opposite shore will be.Hey, hey, L.B.J., how many kids did you kill today?It takes a licking but keeps on ticking.

When you need an edge, use Pledge.

Lean Cuisine, Reese’s Pieces, Ronald McDonald

Why is rhyme so pleasurable?

One theory is that humans like anything that purifies the basics of their world and that resonates with the way the brain decodes the blooming, buzzing confusion out there. We like stripes and plaids, we like periodic and harmonic sounds and we like rhymes.We don't have to work so hard to understand rhyme.

This gives the phrase what psychologists call "fluency." Research in this area tends to point to the fact that messages that are more fluent are not only more memorable, they’re also perceived as being truer. They’re memorable because they are processed more easily. That ease of processing makes them easier to recall. And of course, messages that you can actually remember are much easier to spread to others.People are more likely to accept a proposition they don't believe if it's presented in rhyme, says Matthew McGlone, Ph.D., a psychologist at Lafayette College in Pennsylvania. Asked whether financial success makes people healthier, almost all of McGlone's subjects disagreed, but "wealth makes health" seemed much more plausible.

Occasionally, rhyme has the opposite effect, however. "It will backfire when an audience has reason to be suspicious of the speaker," McGlone says. "

For instance, Cochran's "if the glove doesn't fit'"line was treated as a rallying cry by African-American newspapers, but as a gimmick by the mainstream press, which for the most part portrayed Cochran as a huckster from the beginning of the trial." Suspicion, McGlone explains, provides the motivation to scrutinize a message more closely -- and to make sure it's as pleasing to the intellect as it is to the ear.Cochran was a successful, wealthy and flamboyant lawyer who liked to say that he worked "not only for the OJs, but also the No Js". Another member of Simpson's "Dream Team" of lawyers was Gerald Uelmen, who came up with the glove doesn't fit phrase, which Cochran borrowed.

If you wish to incorporate rhyme in your speaking or writing, remember that Cochran was a showman. It was in character for him to do this. Moreover, the glove was a central part of the case; the rhyme was not manufactured and forced to fit. As it were.